Over the years I have noticed that there is some confusion as to what each are, what they do and when you need them. This article is written to clear things up.

To start, the vapor/compression cycle of typical air conditioning is this: Heat transfers from the space to the evaporator coil and refrigerant in the evaporator will turn to gas. That gas makes it to a compressor which will compress the gas and because pressure and temperature are directly related, the higher pressure means higher temperature. This higher temperature is higher than the ambient temperature, so on a 95 degree day, the condenser coil at 120 degrees will ultimately reject heat. That rejection will allow the condenser gas to become back to a liquid which then travels to an expansion device (ie, TXV) which will drop the pressure of the liquid to allow the refrigerant to evaporate in the coil, repeating the cycle all over.

Back in the day as well as in the present, many air conditioning products would have a scroll compressor and if the size was small enough (typically 5 tons and less), there would only be 1. The compressor would be on or off. While the end user could turn the thermostat all the way down, the result would be the same as one who hits the elevator button 1 time or 1000X- no difference in performance. When that 5 ton system was laid out, it was based on the worst case scenario (95 outside, maximum occupancy, etc). On every other day (84 degrees and ½ the people on vacation for example), the unit would simply “hunt”; unit would come on, maybe overcool (getting that “cold and clammy”) and then wait until it got too warm and try again.

Hot-Gas bypass allows the unit to run better at off peak conditions. Because temperature and pressure are directly related and “too much heat transfer” would occur on a non-peak condition, a bypass valve would literally bypass the refrigerant from the supply of the evaporator back to the return of the compressor, bypassing the coil. In effect, that 5 ton compressor would be doing 5 tons of work but netting, say, 3 tons of capacity. This would get the job done, although not in an efficient way.

As technology advanced, the application of hot-gas bypass can be updated with a modulating compressor. A modulating or variable capacity compressor can be inverter driven (speeds up/down to appropriate performance) or a digital compressor (a very fast series of on and off like a computers 1 and 0). They both have their pros and cons and will require a bit more on the controls end as hot gas bypass has been sequenced from self contained electromechanical controls based on the pressure-temperature theory mentioned above.

This should not be confused with low ambient control. Low ambient is the ability to operate mechanical cooling at full capacity when the temperature outside is well below design. Just as too much heat transfer on the inside can cause low leaving temperatures, too cold outside will cause too will also cause head pressure problems on the system as well. Low ambient controls can be operated by either fan speed control (slow/stop the fan to impede heat transfer), or better a flooded condenser (divert refrigerant into filling the condenser coil with liquid so there is no way heat transfer can occur)

The best scenario to explain is this: If you have a conference room completely jammed with people on a cold winter day, would need a low ambient controller as the cooling load is max but on a low ambient condition. If that conference room was 10% full on an 84 degree day, you would want hot-gas bypass (or a modulating compressor) and the low ambient controller would not be needed.

Hot-Gas reheat is effectively the condenser coil as described in this articles beginning and it is typically used for dehumidification. If you have a mild day and run the air conditioner, the only way to remove moisture is to cool the air (refer to psychometrics for the common man article on our website), but if the air is not warm enough, you will create a cold clammy situation. By using a hot coil, you wring the water out on the evaporator coil and then reheat the air on that second coil, providing neutral dry air. A lot of people think the hot-gas reheat dehumidifies but it’s really the cooling coil doing the work.

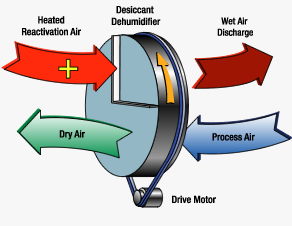

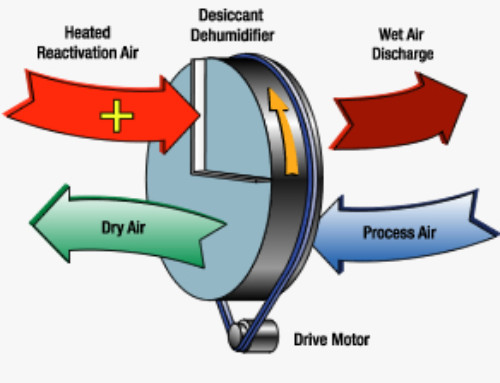

Additionally, the hot-gas reheat is not the only way to dehumidify as there is also a desiccant process for more industrial applications.

ALLOW US TO HELP YOU IN YOUR APPLICATION CALL 973-536-2220 FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION!

How To Remedy A “Cheap” Indoor Pool HVAC System

THE GOOD BETTER BEST OF DEHUMIDIFICATION

CONTACT US